On February 7 the Russian people will welcome the opening ceremony of the Sochi Winter Olympics. The ceremony will celebrate the proud sporting tradition of Russia, and focus on the Winter Games, but it will all take place without two-time Olympic wrestler and legend, Besik Kudukhov.

On December 29, 2013 Kudukhov lost his life when the car he was driving to Krasnodar collided with a truck outside the city of Amariv. Kudukhov was traveling to carry the Olympic torch through Krasnodar and onward to Sochi – a city only a few hundred miles away from his childhood home in Beslan.

Kudukhov had earned the torch-carrying honor after a five-year run as the world's most dominant wrestler.

Kudukhov had won world championships in freestyle wrestling in 2007,2009, 2010 and 2011. He made the podium at two Olympic games, winning a bronze medal in 2008 and the silver in 2012. Though disappointed by his loss in the finals of the 2012 Games, he did not let the defeat put an end to his aspirations to obtain the sport's greatest prize, and all indications pointed to another attempt to win the Olympic gold that had eluded him.

At only 27 years of age, his best competitive years were likely still in his future.

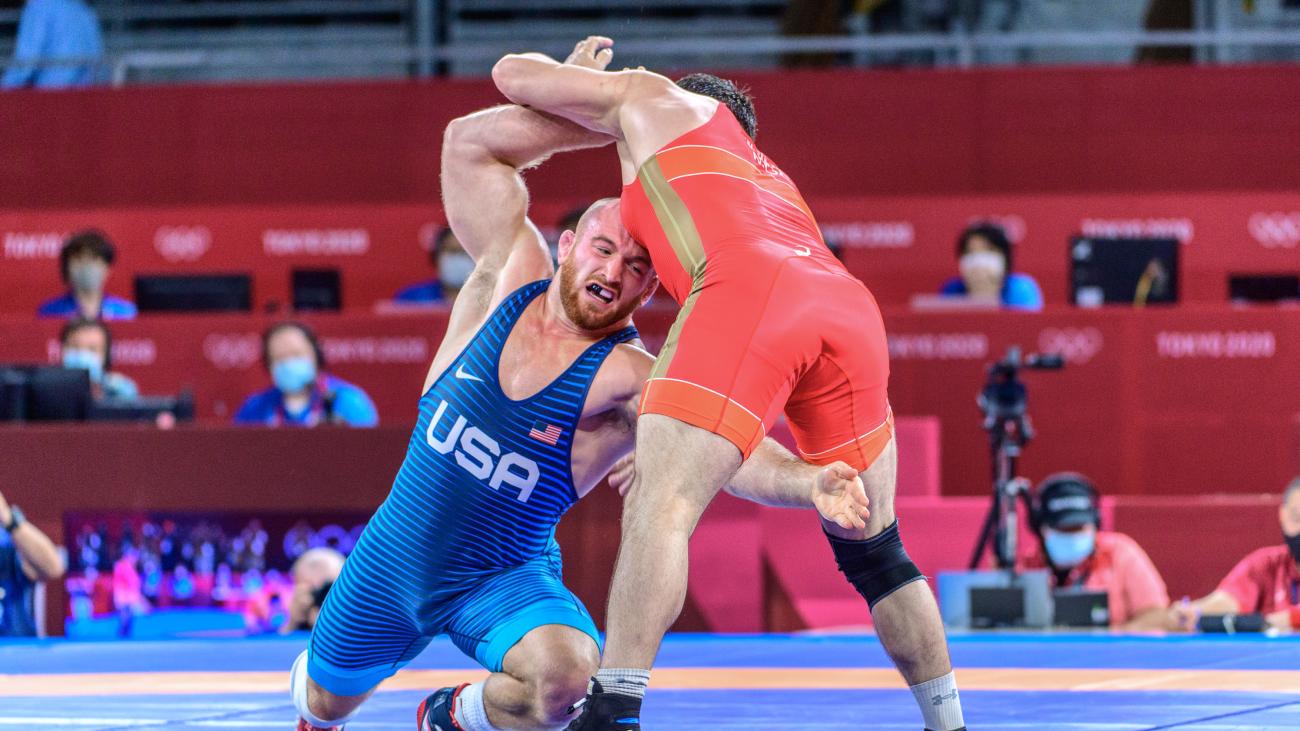

Though his life was cut short by tragedy, Kudukhov left a large footprint on the sport of wrestling and influenced the lives of people around the world. Among those profoundly affected by the life and death of the young Russian, is 2008 Olympian Andy Hrovat of the United States, who trained in Kudukhov's homeland while preparing for the London Olympics.

Hrovat first met Kudukhov in Russia in 2010. Unhappy with his performance wrestling for the United States in the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Hrovat decided to adopt a radically different approach in preparing for the 2012 Games. American wrestling had fallen on hard times -- the USA only had one medalist in 2008 and wasn’t trending well. Meanwhile Russia enjoyed more success on the mats than any nation on the planet. North Ossetia, a subject republic within the Russian federation, bore a particular responsibility for producing a large number of Russia's wrestling stars. Despite a total population of slightly more than 700,000 people, one in five men's freestyle medalists in the Beijing Olympics claimed North Ossetia as their home. The combined efforts of the Americas, Africa, Oceania, and Australia could only muster one medal in freestyle in 2008, but a tiny republic in the Caucasus mountains, roughly the size of the island of Cyprus, won seven. Hrovat decided that he wanted to share in the secrets of the Ossetian success and left his home in Michigan and traveled to the capital of North Ossetia, Vladikavkaz in January 2009.

Upon his arrival to Vladikavkaz, Hrovat became taken with the popularity of wrestling among the city's population. In the United States, even the best wrestlers garner little fame. They go through their competitive careers anonymously, unnoticed by the public at-large, who generally know little to nothing about the sport. Vladikavkaz, however, seems to inhabit some sort of parallel universe where wrestling is king, and wrestlers stand foremost among athletes in the minds of the people. Once, in a taxi ride through the city, the driver discovered the Hrovat came from America, and he began to ask him about American wrestling legend, and 1984 Olympic gold medalist, Dave Schultz, a name known by very few people in the United States.

Hrovat trained in the North Ossetian system, and began to learn their approach to the sport. He found that their success came from consistency in method -- Ossetian wrestlers receive the same program of instruction from a young age till adulthood. Soon, he became an admirer of the elegance of the pedagogy used to teach young athletes in Ossetian wrestling rooms, as well as their single minded focus on producing wrestlers capable of winning world and Olympic championships.

“They have been doing it the same way since the 1930's,” Hrovat said, discussing the secrets of North Ossetian wrestling success. “Their training is just really sport specific for wrestling, and the way they go about doing it, it's just perfect for growing as athletes and growing as wrestlers.”

During his time in Vladikavkaz, Hrovat met world champion, and Olympian, Irbek Farniev. The two struck up a fast friendship, and Farniev mentored Hrovat in strategy and mental preparation for wrestling matches. Farniev enjoyed a close friendship with Kudukhov, whom he helped to coach and train, and through Farniev, Hrovat met Kudukhov. Hrovat knew of Kudukhov's accomplishments as an athlete before their meeting. By then the winner of two world championships at two different weights, Kudukhov already received wide recognition as one the world's best pound for pound wrestlers. What Hrovat did not know, however, was how much Kudukhovs style as a wrestler, his constant energy and unceasing motion, reflected in his personality.

“He was the same off the mat as he was on it, he couldn't sit still, he was always moving,” Hrovat described his impression of Kudukhov.

“He had a happiness to him.""

Hrovat liked Kudukhov immediately, and the two spent time together away from the mats. Though a world champion at the age of 22, Kudukhov never let success go to his head. His generosity and hospitality impressed Hrovat, who marveled at how kindly Kudukhov and his Ossetian kin treated him, a stranger in their land.

Hrovat did not just marvel at Kudukhov's magnanimity. The young Ossetian possessed a level of athletic prowess that the American had rarely ever seen. In training and preparing for competition, Kudukhov clearly displayed the unique talents and amazing physical abilities that allowed him to enjoy such a sustained period of success in wrestling.

“I once saw him do three once-armed pull ups in a row, the real kind."" Hrovat remarked. “You could just see it in the way he moved around on the ropes [hanging in the wrestling room] Nobody could do it like Besik.”

While training together Kudukhov and Hrovat discussed their favorite wrestlers and the athletes that most influenced their performance on the mat. Though Kudukhov had an almost endless supply of stand-out countrymen to point to as his primary role model, he admitted that he had found inspiration from a foreign source.

“He said the wrestlers he most admired were the Brands brothers. He said they were tough guys, and he liked that,” Hrovat recalled. “He even gritted his teeth and made a face [impersonating the Brands brothers].”

The Brands brothers won world championships and Olympic medals for the United States in the 1990’s, while Kudukhov was still a teenager. Their name became synonymous with intensity, combativeness, rigorous training and an aggressive style of wrestling. The Brands' influence manifested clearly in how Kudukhov conducted himself on the mat. Kudukhov became renowned for wrestling offensively and with passion. He pressured his opponents and when he won a big match, like his dramatic world finals victory in 2010, he celebrated with jubilance.

Kudukhov stood out as one of wrestling's most exciting stars in a period where the sport performed poorly. During the dismal days of the 2004 to 2013 iteration of the rules of Olympic wrestling (rules which lent to wrestling’s removal from the Olympics) Kudukhov's still managed to win.

""He'll always be remembered as one of the greatest wrestlers we've ever had, he will be remembered as a bright spot during a dark time for the sport""

Wrestling fans should also remember him as a person who selflessly gave back to the sport. This past summer in Vladikavkaz, at a training camp for the University World Championships, Hrovat approached Kudukhov and asked if he wanted to participate in a private work out with a promising young American wrestler named Nico Megaloudis, The Ossetian gladly accepted.

Megaloudis looked up to Kudukhov as a hero. So there, in one of the world's capitals of wrestling, a young American practiced wrestling with his Russian idol, who in turn modeled his wrestling after the style of two Americans.

Wrestling can bring cultures together, and Kudukhov often acted as the sport’s finest ambassador.

Kudukhov's death does not just leave a hole in the wrestling community. He leaves behind his coach, Farniev, close to him as a brother. He leaves behind his young wife, Christina, and a one-year old daughter. He leaves behind his beloved mother, Leila, whom he has supported since his father's death 12 years ago, and he leaves behind the people of North Ossetia who adored him.

When asked about what Kudukhov meant to his country and all the people who loved him, Hrovat answered succinctly

“He's a legend.”

Fortunately, for all those who dearly loved Kudukhov, legends never die.