India's Phogat sisters are at the forefront of the battle to improve female wrestling around their home country

"Give me the phone,” Babita said as she slumped on the bed, exhausted after her practice session.

“Wait” Vinesh signaled to her, raising a finger to her lips. On the other end, it was Vinesh’s adopted father Mahavir Phogat, and he was just delivering his parting shot: “Get the gold medal, or else I will beat you up with a stick when you get home.” Vinesh winced, then smiled, “Ok, ok,” she said on the phone, “Now talk to Babita.”

Babita wanted to speak to Geeta. “Not you papa. I need to ask Geeta something,” she said.

When Geeta came on the phone, Babita told her that a ligament on her left knee was hurting—she had gone and met a doctor and had an MRI done.

“How much does it hurt? Geeta asked.

“Not much,” Babita said, but Geeta had already heard the hesitation in her voice.

“Don’t lie!” Geeta said.

Babita felt like sobbing. “The doctor said that I can’t fight in this condition.”

“Well…”

“But I told him, no matter, I will fight,” Babita said, the words coming out in a rush. “I don’t care how bad the pain is, if I can stand, if I can move, I am fighting. It’s ok if I lose. But I am not coming back without getting on the mat.”

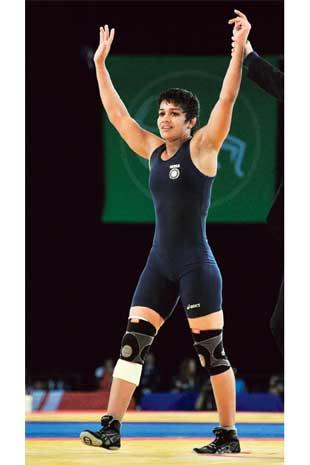

Vinesh was spared the stick: She won a gold in 48kg Freestyle wrestling at the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow on 29 July, two days after she and her cousin-sister Babita had spoken to Mahavir. Two days after that, still battling her ligament injury, Babita won a gold medal in the 55kg weight-class. Two sisters from the Phogat family, both on the podium for wrestling—it was not even the first time this had happened. They had done this at the 2010 CWG in Delhi too, except it wasn’t Vinesh who was on the medal list with Babita, but Geeta, the oldest of the Phogat girls.

Vinesh was spared the stick: She won a gold in 48kg Freestyle wrestling at the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow on 29 July, two days after she and her cousin-sister Babita had spoken to Mahavir. Two days after that, still battling her ligament injury, Babita won a gold medal in the 55kg weight-class. Two sisters from the Phogat family, both on the podium for wrestling—it was not even the first time this had happened. They had done this at the 2010 CWG in Delhi too, except it wasn’t Vinesh who was on the medal list with Babita, but Geeta, the oldest of the Phogat girls.

There are six of them—Geeta, Babita, Ritu, Vinesh, Priyanka, Sangeeta—in that order. Vinesh and Priyanka are the daughters of Mahavir’s brother, who was killed in a dispute 10 years ago. Since then the two girls have lived with Mahavir’s family. They are all wrestlers. And what if all of six of them land up in the same competition one day, and all of them finish with medals?

“Let that be the Olympics!” Babita is thrilled with the idea. It has occurred to her before, as it has to Geeta. “Well, perhaps not all six. Let’s say three,” Geeta says. “Now that’s not fantasy—that can happen in Rio.”

“Yes, and then papa will finally say”—Babita makes her voice heavy and manly—“good, you have done well. Now you can rest a little.” The sisters laugh with abandon.

Babita and Vinesh are back in training, this time for the Asian Games in Incheon, South Korea. Geeta is recovering from a surgery to fix the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) on her right knee, but she is at the camp to look after her sisters and coach them even as she does her own rehab work.

Geeta is a gentle, soft-spoken woman with an aquiline nose and an easy smile. She is the only one of the six sisters with long hair, which she ties in a high ponytail during her bouts. The rest have identical short crops that barely cross the nape.

As the eldest sister, Geeta has forged a remarkable path for the rest to follow—a CWG gold in 2010 was followed by a bronze at the 2012 world championship, a first for Indian women; that same year she also became the first woman from India to qualify for wrestling at the Olympics; in 2013 she won all but one of her seven bouts at the Women’s Wrestling World Cup, finishing second—and it began in a village called Balali in Haryana.

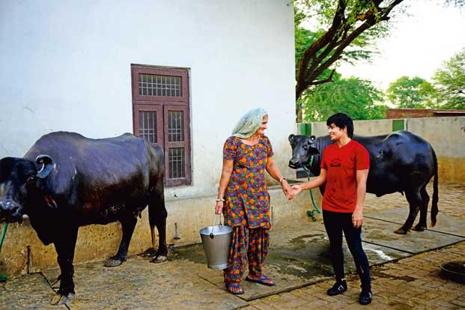

Balali is deep country. It is still untouched by Haryana’s hurried pace of urbanization, and sits hidden in the middle of wheatfields and guava and citrus groves. In the afternoon, you can walk around Balali’s slim tracery of cobbled streets and meet not a single person.

Inside Mahavir’s house—an elongated rectangle of flat white—there is a stirring of post-siesta activity. Mahavir is on his charpoy, eyes still resolutely closed. There is a gathering of village elders, all in white kurtas, who have lit the communal hookah and broken out the cards. Mahavir’s wife Daya has swung into action. The family’s immense black buffaloes have been led out of the shed, their troughs filled with feed. Daya is laying out the buckets she will use for milking.

Mahavir opens his eyes abruptly, pulls out his phone and scolds someone at the other end: “Where’s your daughter? We start in five minutes. Tell her to run.” He stands up and shuffles towards the house. It’s not a house. It’s a large wrestling hall: A double-sized mat on one side, top-of-the-line weight machines in another, thick ropes dangling from the high ceiling, and a series of small windows overlooking lush farmland. Ritu, Sangeeta, and Priyanka walk in, dressed in dry-fit Ts and training tights. Two more girls come running in. Then two boys. “Warm up!” Mahavir barks, pointing at the mat.

Mahavir opens his eyes abruptly, pulls out his phone and scolds someone at the other end: “Where’s your daughter? We start in five minutes. Tell her to run.” He stands up and shuffles towards the house. It’s not a house. It’s a large wrestling hall: A double-sized mat on one side, top-of-the-line weight machines in another, thick ropes dangling from the high ceiling, and a series of small windows overlooking lush farmland. Ritu, Sangeeta, and Priyanka walk in, dressed in dry-fit Ts and training tights. Two more girls come running in. Then two boys. “Warm up!” Mahavir barks, pointing at the mat.

That there are girls wrestling at all, in these rural settings, is in itself a miracle, let alone the quality of international success they have managed. Ritu, 20, has two golds and a silver at the Asian Wrestling Championships for cadets, a bronze from the cadets World Championship, a Junior World Championship bronze, a Junior World Championship silver this year, and a Junior Asian Championships gold. Sangeeta, 15, made her debut at the Asian Championships for cadets this year and won a silver. Priyanka, 20, has a gold and a silver from the Asian Championships (cadets).

That these women live in Haryana is even more surreal. The state has the worst sex ratio in the country according to the 2011 census—879 women for every 1,000 men; and while it is in the top 15 states for male literacy, it is firmly in the bottom five for female literacy. Women in rural Haryana keep their heads covered in view of men, and are largely excluded from public life. The sport of wrestling, steeped in tradition, is in itself a symbol of this: It is considered an exclusively male bastion, where women even stepping into an akhara can be seen as provocative. There are thousands of akharas in India, and almost all of them are meant only for men, including Delhi’s famous Chatrasaal akhara, which has produced the likes of world champion and Olympic medalist Sushil Kumar, Olympic medalist Yogeshwar Dutt, and world championship medalists Amit Kumar and Bajrang. While Chatrasaal stadium itself runs various sports training programmes for boys and girls, the wrestling school is meant only for men.

Only the training centres run by the Sports Authority of India do not discriminate, by law. And then there are the little pockets of resistance—Balali and the Phogats; Meerut, where renowned coach Jabbar Singh Sone trains girls from the most impoverished of backgrounds; Indore, where former Olympian Kripa Shanker Patel campaigns for akharas to open their doors to women and runs his own centre; Rohtak, where the University of Rohtak runs a popular training centre; and former Olympian Prem Nath’s akhara in Delhi.

Only the training centres run by the Sports Authority of India do not discriminate, by law. And then there are the little pockets of resistance—Balali and the Phogats; Meerut, where renowned coach Jabbar Singh Sone trains girls from the most impoverished of backgrounds; Indore, where former Olympian Kripa Shanker Patel campaigns for akharas to open their doors to women and runs his own centre; Rohtak, where the University of Rohtak runs a popular training centre; and former Olympian Prem Nath’s akhara in Delhi.

“The general atmosphere is still strongly against women in wrestling,” says Kripa Shanker, who is also one of the coaches with the national women’s team. “We have a very small talent pool to pick from. Maharashtra, which produces hundreds of male wrestlers, has nothing for women, Madhya Pradesh has very little, Jabbar Singh is alone in Uttar Pradesh. Only Haryana is really trying. Women’s wrestling is still new to the world, and we could have stepped ahead, taken the lead, and dominated it for years. But no, we are stuck being backwards, judgmental and idiotic.”

Even though women’s wrestling was made a part of the Olympics in 1997 (but first included in the Games in 2004), and had its first national championship in India in 1999, there are only 337 women wrestlers registered with the Wrestling Federation of India; the men number a neat 2,999.

Women are also informally barred from the thousands of rural dangals that happen across India through the year.

“Yes, traditionally, dangals and akharas are not considered fit places for women,” says Kamala Devi, Sushil Kumar’s mother. She has never gone to see her son fight.

Blurred Lines

Geeta remembers the odd morning when her father woke her and Babita up at five one morning and said, “I want to see how well you two run.”

Geeta remembers the odd morning when her father woke her and Babita up at five one morning and said, “I want to see how well you two run.”

She was 10 then, Babita 8, and they were both a bit puzzled.

“It was fun though,” Geeta says. “We ran laughing through the fields when everyone else was asleep, it felt like a secret game.”

A week of that, and Mahavir in the meantime had finished making a level square of soft earth next to his house, raising a tin shed over it. The akhara was ready. “People said, Mahavir has lost his mind,” he says. “They said, he is destroying the village, he has no shame, and he is making an exhibit out of his own girls.”

But there was only so much the villagers could do to oppose this unprecedented development—Mahavir was the sarpanch, and the family had both influence and land. “So we were spared the worst of it,” Daya says, “they could not come up to me and say these things on my face. But I was told many times, ‘your daughters will become like boys, their faces will get messed up, they won’t be able to bear children, their ears will get mangled, and who will marry them?’ I felt the stress of that. But I felt angry that there was so much opposition to the girls doing anything different, so I wanted to see the fight through the end.”

Geeta and Babita was exposed to some of this harassment, and they would often see their parents engaged in heated arguments with neighbours and extended family. They would be stared at coldly, people who would greet them before, talk to them, would not even make eye contact.

“After a few months, there were a couple of boys at the akhara as well, and papa started training us together, we would fight the boys, and wrestling’s such an intimate sport,” Babita says, “that was a step too far for most people in the village, there was constant trouble during that time.”

There were four other girls of Geeta and Babita’s age who joined the akhara when it started. Within a month, their parents buckled under the social pressure and pulled them out. “Now they rue that day,” Mahavir says. “I used to tell them, if a woman can become Prime Minister and run the country, if a woman can be a sarpanch, a doctor, then why can’t she be a wrestler?”

The Phogat girls loved the life of the wrestler—the pain, the euphoria, the fighting and sleeping exhausted after a hard day’s training, the liberating experience of wearing shorts and t-shirts, all the fuss over their diet—“It was a great adventure,” Babita says, “And what made it special was that we knew no other girls in our village or in any nearby village that was doing this!”

A Light is Switched On

If you trace the careers of all the wrestling coaches who now work with women, the lines converge and meet at one place: In Delhi, in a house and an akhara on the banks of the Yamuna. From the highway that goes past it, the low, unassuming structure of the house is hidden by trees. This is Chandgi Ram Vyamshala, named after its late founder, a legendary wrestler and coach who had won the heavyweight gold at the 1970 Asian Games, as well as every major traditional kushti title in India. He also dabbled in films, starring in three Hindi movies in the 1970s, and lived with three wives. After representing India in the 1972 Olympics in Munich Chandgi Ram settled down in Delhi, and opened an akhara. He had three daughters and two sons from his wives, and in the 70s and 80s, his akhara was second to none in popularity. While the brothers grew up in the akhara, the girls were banned from it.

If you trace the careers of all the wrestling coaches who now work with women, the lines converge and meet at one place: In Delhi, in a house and an akhara on the banks of the Yamuna. From the highway that goes past it, the low, unassuming structure of the house is hidden by trees. This is Chandgi Ram Vyamshala, named after its late founder, a legendary wrestler and coach who had won the heavyweight gold at the 1970 Asian Games, as well as every major traditional kushti title in India. He also dabbled in films, starring in three Hindi movies in the 1970s, and lived with three wives. After representing India in the 1972 Olympics in Munich Chandgi Ram settled down in Delhi, and opened an akhara. He had three daughters and two sons from his wives, and in the 70s and 80s, his akhara was second to none in popularity. While the brothers grew up in the akhara, the girls were banned from it.

“We (the sisters) had a free, fun-loving childhood,” says Sonika Kaliraman, the second daughter. “I was nature’s child, chasing frogs on the riverbank, spending hours watching spiders weaving webs.”

In 1997, when the announcement was made that women’s wrestling would be inducted into the Olympics, this idyllic life changed. “I remember that I was playing with a tap in the courtyard, spraying water on the plants,” says Sonika. “And father came back home looking all excited and the first thing he said was ‘they’ve put women’s wrestling in the Olympics! Who wants to be a wrestler?’ And he was looking straight at me.”

Sonika was flummoxed. She had been a laughing stock in school sports. She was tall and well-built for her age, but uncoordinated, which tickled other students and parents. “I was always the joker of the pack,” she says. “I was a…what do you call those funny animals? Sloths! I was a sloth—slow, shuffling, baby fat—so when he said this, I was like, yes! I want to be a wrestler!”

Deepika Kaliraman, a year older to Sonika, was less enthusiastic. So one day Chandgi Ram bundled both his daughters into an auto rickshaw and took them to an a state-run sports training centre, which had been instructed by the government to train their Judoka girls in the basics of wrestling.

“It was the weirdest thing—girls wrestling!” Deepika says. “It was funny, scary, liberating, elating, all at the same time. We laughed at the ‘costumes’—we had never seen girls dressed in shiny body-hugging clothes. Look at those muscles! Those thighs! As we were taking it all in, one of the girls picks up another over her hip and slams her down on the mat—BAM—and it was like a dazzling light switched on in our brain.”

The two sisters now joined their brother Jagdish Kaliraman on the wrestling pit, and Chandgi Ram began his campaign. “At six in the morning papa would sit in front of the phone and start calling coaches and wrestlers all over India,” Deepika says. “He would say, ‘look the boys of my akhara will only come to your dangal if you allow a girl’s bout as well—just a couple of exhibition matches.’ He had a lot of patience and a lot of drive. He would call, write letters, and meet people all day with just agenda, start getting women into wrestling.”

Jagdish, Deepika and Sonika were constantly on the road, from city to city, village to village, dangal to dangal. “We forgot everything but wrestling,” Sonika says. “I forgot Diwali, my animals, friends. For the next 10 years, there was time for nothing but wrestling.” The band of wrestlers traveled with their home on their backs, clothes, utensils, stoves, fuel, bundled into army holdalls.

Jagdish, Deepika and Sonika were constantly on the road, from city to city, village to village, dangal to dangal. “We forgot everything but wrestling,” Sonika says. “I forgot Diwali, my animals, friends. For the next 10 years, there was time for nothing but wrestling.” The band of wrestlers traveled with their home on their backs, clothes, utensils, stoves, fuel, bundled into army holdalls.

They practiced in trains and train stations and farmlands.

The backlash was severe. As Chandgi Ram’s campaign grew more heated, the counter-campaign did too. The family faced personal attacks. Their morality was questioned. Wrestlers at his own akhara revolted.

“When Sonika and Deepika started doing exhibition bouts, people used to come just to see the fun, the freak value, to get their fill of fantasy,” Jagdish says. “They would be disappointed to see that the girls fought just like anyone else—with technique and skill and power.”

There was violence as well—attacks on Chandgi Ram’s akhara, as well as at dangals. “One time in 2000 we had gone to a dangal in a village in Palwal,” Deepika says. “It was a clearing in the middle of a sugarcane farm. The moment Sonika and I got on to the pit, stones started flying at us, and people were shouting and surging towards the pit, some brandishing sticks.

“Papa rushed at us,” Deepika says, slapping her thigh hard with the palm of her hand. “We ran helter skelter. Papa bundled us into the car, and we drove off with people chasing. We’ve got all kinds of ‘warm receptions!’”

Chandgi Ram and his family soldiered on. In 2001, both Jagdish and Sonika won at Bharat Kesri—India’s biggest wrestling title—Chandgi Ram had won it too; just like all three of them also held the title of national champion at various stages of their careers. Deepika had to give up wrestling after an injury, but Sonika and Jagdish represented India at the Asian and World Championships. (Sonika retired in 2011 and moved to Los Angeles with her husband; Deepika runs a wrestling school for girls and boys in Delhi, and heads the All India Women’s Wrestling Association, which helps women with legal counselling.)

Chandgi Ram and his family soldiered on. In 2001, both Jagdish and Sonika won at Bharat Kesri—India’s biggest wrestling title—Chandgi Ram had won it too; just like all three of them also held the title of national champion at various stages of their careers. Deepika had to give up wrestling after an injury, but Sonika and Jagdish represented India at the Asian and World Championships. (Sonika retired in 2011 and moved to Los Angeles with her husband; Deepika runs a wrestling school for girls and boys in Delhi, and heads the All India Women’s Wrestling Association, which helps women with legal counselling.)

In 2010, Chandgi Ram died, his battle only half-finished, but he had found people to take it forward.

Jagroop Rathi, one of Chandgi Ram’s co-coaches, brought his daughter Neha to the akhara—she became an international medal winner. Jabbar stayed at Chandgi Ram’s akhara for a few months of training and went away transformed, beginning his long battle to get women into the sport. His trainee Alka Tomar became the first Indian woman to win a wrestling medal at the World Championships in 2006. Her sister Anshu Tomar became an international wrestler. Yet, just last year, a village panchayat near Meerut banned its girls from wrestling, and Jabbar lost four students.

Geetika Jakhar, who is the first Indian woman to win a silver medal in wrestling at the Asian Games (in 2006) comes from Hisar, Chandgi Ram’s town, and one of the places where he campaigned the most. After two years out with an injury, Geetika won a gold at the 2014 Commonwealth Games and is part of the 4-member team traveling for the Asian Games along with Babita, Vinesh, and Delhi wrestler Jyoti.

Mahavir was 16 when he first came to Chandgi Ram’s akhara, and quickly became one of his favourite students. “Masterji opened my eyes,” Mahavir says. “He used to tell me, “what you are doing for your girls, you will see one day that it will bring you great happiness. So keep doing it, don’t be scared, face your difficulties like you face opponents, and be deaf to the criticism.”

The Olympic Way

The struggle is still on. Women’s wrestling at dangals is still restricted to an exhibition bout at best, though the resistance to has tempered down. Since 2006, women and men have been getting the same cash awards and the same funding from the government at the international level, but not the same facilities. While the international men’s team train at the state-of-the-art SAI centre at Sonepat, tailored exclusively for wrestlers since 2010, the women train at SAI’s Lucknow centre, meant for junior athletes.

The struggle is still on. Women’s wrestling at dangals is still restricted to an exhibition bout at best, though the resistance to has tempered down. Since 2006, women and men have been getting the same cash awards and the same funding from the government at the international level, but not the same facilities. While the international men’s team train at the state-of-the-art SAI centre at Sonepat, tailored exclusively for wrestlers since 2010, the women train at SAI’s Lucknow centre, meant for junior athletes.

“We have no doctors here,” says Babita. “If we have an injury, the nearest medical care is half an hour’s drive, at a government hospital where we wait in queues for 1-2 hours before we get to see a doctor.”

The wrestling hall is not air-conditioned, and both wrestlers and coaches have repeatedly complained about the poor quality of the food. High performance training this is not.

Geeta blames this for her injury—she says the physio with the women’s team is not qualified to work with athletes, and misjudged the severity of her injury. “He told me that I should continue training, and I did, and then my knee was gone,” Geeta says. “After that I had no medical care. It’s only when my sponsors, JSW, flew me to Mumbai and got me checked that the treatment started.”

Mahavir is hurt by this apathy, but tries not to think about things he has little control over. Instead, he pours his energy into training. It’s on in full swing in his akhara. Ritu is battling Ankesh, a 14-year-old boy who is the son of a sweeper employed by the government, and started training a year back. Ritu is quick and fluid. She swivels with Ankesh’s arm in a lock, and throws him over her shoulders and onto the mat. BAM!

Ritu is waiting to make her breakthrough in the senior team after winning every international cadet and junior championship that exists. “We have been lucky,” she says, “Because of Geeta-Babita, we did not face any hurdles. We have traveled the world—Hungary, USA, Indonesia, Romania, Croatia, Thailand. The Olympics is not some distant dream. I am preparing for that, the qualifications start next year.”

Mahavir dreams of Olympic gold. Not silver, or bronze, there can be no compromise. He drills this into his girls.

In 2010, when Geeta won India’s first CWG gold in women’s wrestling, Balali went berserk. The celebrations lasted 10 days. No one ever says that women should not be in wrestling anymore. The word has spread to nearby villages. So many girls started coming for training that Mahavir had to build a hostel for them—36 girls live there now. The girls in Haryana, Rajasthan, Punjab are big and strong, says Mahavir, and they will take women’s wrestling very far. “Just don’t hide them at home,” he says. “When I was growing up, girls did not go to school here. Now every single one in the village is working for a college degree. So things are changing. The future of sports is in their hands. This year at the CWG, India won 65 medals; 49 of those were won by women. There is no other argument here. Nothing more to say.”

-

This story originally ran on Live Mint and was written by Rudraneil Sengupta, (rudraneil.s@livemint.com). Please send all emails to the author and refer to the link below for the original piece.

http://www.livemint.com/Leisure/HSkIGQCBJHTNWx91UgibbM/Gender-Six-ways-to-break-the-shackles.html