5 رویداد برتر ماه نوامبر/ 6 قهرمان جهان در جام جهانی تهران

جمعه, نوامبر 8, 2019 - 10:07 By Eric Olanowski

مروری بر نتایج مسابقات زیر 23 سال جهان و بررسی مسابقات پیش رو در جام جهانی زنان و جام جهانی کشتی فرنگی.

1- دفاع ستاره ظهور کرده مصر از قهرمانی اش در مسابقات جهانی زیر 23 سال

10 روز. این مدت زمانی بود که طول کشید تا محمد السید از مصر رزومه اش را با دو عنوان جهانی بهبود بخشد. در کمتر از دو هفته، این ستاره نوظهور 21 ساله مصری مسیر خود را به سوی سکوی افتخار هموار کرد و در مسابقات زیر 23 سال جهان و ارتشهای جهان قهرمان شد.

السید از اکتبر 23 مسیر فوق العاده خود را از مسابقات نظامیان جهان در ووهان چین آغاز کرد و در وزن 67 کیلوگرم قهرمان شد. سپس او همانند مسابقات نظامیان، 5 رقیب را نیز در مجارستان از پیش رو برداشت و قهرمان زیر 23 سال جهان شد و از مدال طلای سال گذشته اش نیز دفاع کرد.

او در مسابقات جهانی نورسلطان نیز با کسب عنوان پنجم، سهمیه المپیک وزن 67 کیلوگرم را نصیب مصر کرد.

Taylor Miller's Greco-Roman Wraps:

Novikov Avenges European C’Ships Loss to Defend U23 World Title

Elsayed Collects Second World Title in Less than Two Weeks at #WrestleBudapest

نتایج فینالهای کشتی فرنگی:

55 کیلوگرم: شوتا اوگاوا (ژاپن) 4 – امین سفرشایف (روسیه) 3

60 کیلوگرم: آرمن ملکیان (ارمنستان) 11 – ژولامان شارشنبکوف ( قرقیزستان) 7

63 کیلوگرم:میثم دلخانی (ایران) 7 – لوانی کاجارادزه (گرجستان) 6

67 کیلوگرم: محمد ابراهیم السید (مصر) 9 – الکساندر لیاونچیک (بلاروس) 0

72 کیلوگرم: محمد رضا گرایی (ایران) 7 – سانان سلیمانوف (آذربایجان) 0

77 کیلوگرم: اسلام اوپیف (روسیه) 3 – کودای ساکورابا (ژاپن) 1

82 کیلوگرم: میلاد آلیرزایف (روسیه) 8 – ویکسلاو لوبوریچ (کرواسی) 0

87 کیلوگرم: سمن نوویکوف (اوکراین) 6 – گورامی ختسوریانی (گرجستان) 1

97 کیلوگرم: آروی مارتین ساوولاینن (فنلاند) 5 – گئورگی ملیا (مجارستان) 3

130 کیلوگرم: علی اکبر یوسفی (ایران) مقابل زویادی پاتاریدزه (گرجستان) به دلیل مصدومیت حریف گرجی برنده شد.

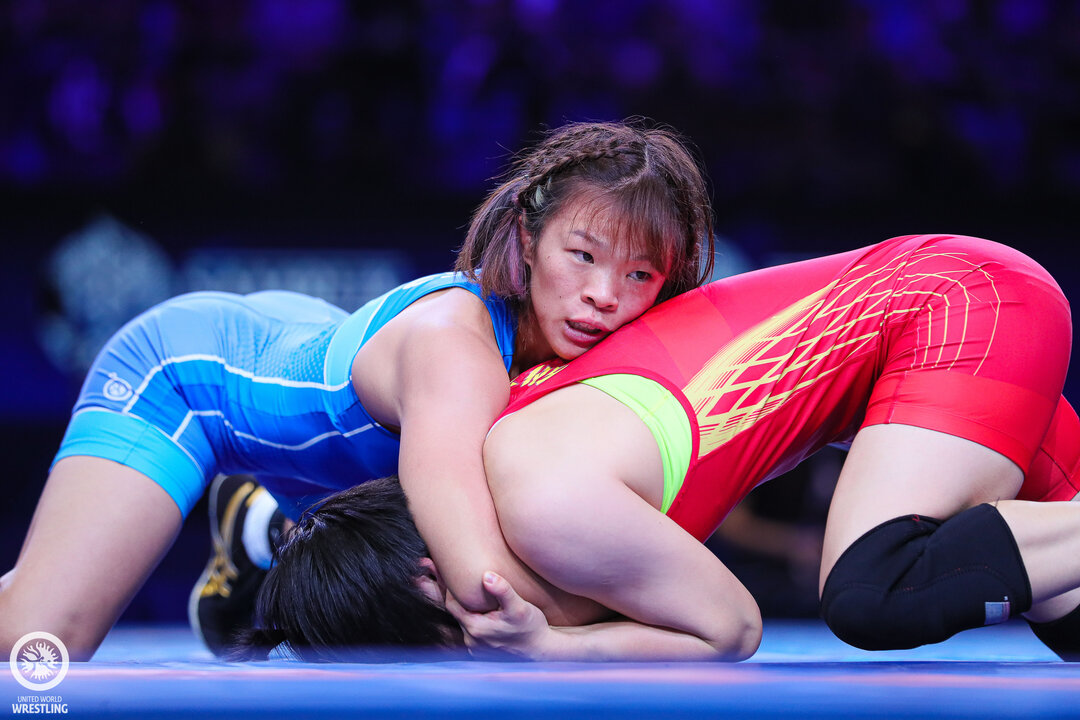

Haruna OKUNO (JPN) was one of seven Japanese wrestlers to win a U23 women's wrestling title. (Photo: Sachiko Hotaka)

Haruna OKUNO (JPN) was one of seven Japanese wrestlers to win a U23 women's wrestling title. (Photo: Sachiko Hotaka)

2- کسب 7 طلای زنان ژاپن در زیر 23 سال جهان از 10 وزن

کشتی گیران زن ژاپن به یک برتری غیر عادی در مسابقات زیر 23 سال جهان رسید و صاحب رکورد 27 برد و تنها 3 باخت رسید تا از 10 مدال ممکن صاحب هر 10 مدال از جمله 7 طلا شود. تیم ژاپن با 125 امتیاز بالاتر از چین 105 امتیازی ایستاد.

کشور خاور دور، در تمامی رده های نوجوانان، جوانان، زیر 23 سال و بزرگسالان زنان جهان صاحب عنوان قهرمانی شد و در همه رویدادها حداقل 6 مدال تصاحب کرد.

Taylor Miller's Women's Wrestling Wraps Wraps:

Marin Potrille Takes Down Senior World Medalist for U23 World Title

Furuichi Wins Seventh World Gold, Paliha Defends U23 World Title at #WrestleBudapest

مدالهای کشتی زنان ژاپن در مسابقات جهانی 2019:

نوجوانان- شش طلا و سه برنز

جوانان: هشت طلا و دو برنز

زیر 23 سال: هفت طلا، دو نقره و یک برنز

بزرگسالان: یک طلا، سه نقره و دو برنز

Razambek ZHAMALOV (RUS) helped Russia claim their fourth freestyle world title across all divisions with an 8-1 victory over Mohammad Ashghar NOKHODILARIMI (IRI) in the 74kg finals. (Photo: Kadir Caliskan)

Razambek ZHAMALOV (RUS) helped Russia claim their fourth freestyle world title across all divisions with an 8-1 victory over Mohammad Ashghar NOKHODILARIMI (IRI) in the 74kg finals. (Photo: Kadir Caliskan)

3- برتری روسیه مقابل ایران در کشتی آزاد زیر 23 سال جهان

فدراسیون روسیه با غلبه بر ایران در مسابقات زیر 23 سال جهان که با اختلاف 6 امتیاز بدست آمد، برای چهارمین بار در سال 2019 به قهرمانی کشتی آزاد جهان در رده های مختلف رسید.

روسیه 6 امتیاز بیشتر از ایران بدست آورد و ایران هم 34 امتیاز بالاتر از آذربایجان رده سومی کسب کرد.

Taylor Miller's Freestyle Wraps:

Zholdoshbekov Claims First Men’s Freestyle World Title for Kyrgyzstan Since 2005

Andreu Ortega and Goleij Claim Second U23 World Titles at #WrestleBudapest

نتایج فینالهای کشتی آزاد:

57 کیلوگرم: رینری اورتگا (کوبا) 10 – ادلان عسکروف (قزاقستان) 0

61 کیلوگرم: اولوکبک ژولدوشبکوف (قرقیزستان) 5 – راویندر (هند) 3

65 کیلوگرم: توران بایراموف (آذربایجان) 3 – تاکوما تانی یاما (ژاپن) 2

70 کیلوگرم: میرزا اسخولوخیا (گرجستان) 7 - چرمن والیف (روسیه) 5

74 کیلوگرم: رازامبک جمال اف (روسیه) 8 – محمد نخودی (ایران) 2

79 کیلوگرم: تاریل گافرینداشویلی (گرجستان) با ضربه فنی ابوبکر آباکاروف (آذربایجان) را شکست داد.

86 کیلوگرم: کامران قاسمپور (ایران) 9 – گاجی مراد ماگومداف (آذربایجان) 3

92 کیلوگرم: بو دین نیکال (امریکا) 12 – باتیربک تساکولوف (روسیه) 2

97 کیلوگرم: مجتبی گلیج (ایران) 8 – شامیل موسایف (روسیه) 2

125 کیلوگرم: امیر حسین زارع (ایران) 10 – ویتالی گولویف (روسیه) 0

Three-time world and Rio Olympic champ Risako KAWAI (JPN) will compete at 57kg at the Women's Wrestling World Cup. (Photo: Kadir Caliskan)

Three-time world and Rio Olympic champ Risako KAWAI (JPN) will compete at 57kg at the Women's Wrestling World Cup. (Photo: Kadir Caliskan)

4- ژاپن برای میزبانی جام جهانی زنان آماده می شود (16 و 17 نوامبر)

برای ششمین بار در 18 سال برگزاری، جام جهانی کشتی زنان به پیروزترین کشور جهان در این رشته باز می گردد. مدافع 4 عنوان قهرمانی جام جهانی، این مبارزات سالانه را 16 و 17 نوامبر در مرکز تفریحی، ورزشی ناکادای در شهر ناریتای ژاپن میزبانی میکند.

ریساکو کاوای از ژاپن و آدلاین گری از آمریکا از جمله 5 مدافع عنوان قهرمانی و 19 مدال آور مسابقات جهانی هستند که در ناریتا به میدان می روند.

5 مدافع قهرمانی جهان در جام جهانی زنان:

55 کیلوگرم: یاکارا وینچستر (آمریکا)

57 کیلوگرم: ریساکو کاوای (ژاپن)

62 کیلوگرم: اینا تراژکوا (روسیه)

68 کیلوگرم: تامیرا منساه (آمریکا)

76 کیلوگرم: آدلاین گری (آمریکا)

Ismael BORRERO MOLINA (CUB) (Photo: Tony Rotundo)

Ismael BORRERO MOLINA (CUB) (Photo: Tony Rotundo)

5- حضور چهره ها در جام جهانی کشتی فرنگی (28 و 29 نوامبر)

ورزشگاه آزادی در تهران، پایتخت ایران به استعدادهای سطح بالای جهان برای حضور در جام جهانی کشتی فرنگی که 28 و 29 نوامبر برگزار می شود، خوشامد خواهد گفت. شش فرنگی کار مدافع عنوان قهرمانی جهان به تهران سفر خواهند کرد تا در جام جهانی کشتی فرنگی مبارزه کنند. اما 67 کیلوگرم، وزنی است که مبارزاتش تماشایی خواهد بود چرا که احتمالا مسابقه فینال المپیک بین اسماعیل بوررو از کوبا و شینوبو اوتا از ژاپن می تواند نگاه ها را به سوی خود جلب کند.

بوررو و اوتا هر دو در مسابقات جهانی نورسلطان قهرمان شدند اما اوتا که در وزن غیر المپیکی 63 کیلوگرم قهرمان شد، قصد دارد به وزن المپیکی 67 کیلوگرم بیاید، جایی که بوررو قهرمان فعلی جهان در آن وزن محسوب می شود.

اوتا کمی پس از قهرمانی جهان اعلام کرد که 4 کیلو اضافه خواهد کرد تا به وزن 67 کیلوگرم بیاید و مدال نقره خود در المپیک ریو را بهبود بخشد؛ رقابتی که در آنجا و در فینال مغلوب بوررو کوبایی شد.

به جز بوررو و اوتا، جام جهانی کشتی فرنگی به چهار قهرمان جهان دیگر نیز خوشامد خواهد گفت: نوگزاری تسورتسومیا (گرجستان)، کنیچیرو فومیتا (ژاپن)، ابویزید مانتسیگوف (روسیه) و لاشا گوبادزه (گرجستان).

جام جهانی کشتی فرنگی 28 نوامبر برگزار می شود که بصورت زنده از سایت اتحادیه جهانی کشتی پخش خواهد شد.

مدافعان قهرمانی جهان در جام جهانی کشتی فرنگی:

55 کیلوگرم: : نوگزاری تسورتسومیا (گرجستان)

60 کیلوگرم: کنیچیرو فومیتا (ژاپن)

67 کیلوگرم: اسماعیل بوررو (کوبا)

67 کیلوگرم: شینوبو اوتا (ژاپن)

72 کیلوگرم: ابویزید مانتسیگوف (روسیه)

82 کیلوگرم: لاشا گوبادزه (گرجستان)

5 رویداد برتر در شبکه اجتماعی

1. Big Move Monday -- Akmataliev E. @akmataliev_ernazar -- U23 Worlds 2019

2. SEFERSHAEV (RUS) gets the win in a crazy match against HALAKURKI (IND) ? .

3. Big throws by FENG (CHN) ?? ? ?♂️

4. GHASEMPOUR (IRI) defeats SADOWIK (POL) will he win the gold again? ? ?? ?

5. Back and forth match between IBRAGIMOV (AZE) and PANTALEO (USA) with IBRAGIMOV grabbing the 9-8 win ?? ? ?

Share your thoughts.

دیدگاهها